Members of akta. Second from the right is Kohta Iwahashi. Photo courtesy of akta.

In recognition of this week’s convening of the 2021 United Nations High-Level Meetings on HIV/AIDS, the Friends of the Global Fund, Japan (FGFJ) is pleased to introduce our interview with Kohta Iwahashi (president of akta) in the latest installment of our collaborative series with Asahi GLOBE+, “Infectious Diseases Without Borders–Our Story.” In the Ni-chome district of Shinjuku, Tokyo, which is home to Asia’s largest gay community, there is a nonprofit organization called akta that has spent the last 20 years providing information on HIV prevention for sexual minorities. Mr. Iwahashi dives into akta’s community-based activities and how we can adopt the experiences and lessons learned from the fight against HIV/AIDS to the COVID-19 fight.

This interview was conducted in Japanese, and translated by JCIE/FGFJ. To read the full version of this interview in Japanese, please visit the Asahi Globe+ website.

Please tell us a little about what akta does.

Our nonprofit organization, akta, operates a community-based facility that promotes HIV prevention and sexual health. With funding support from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW), akta was officially created in 2003 to raise awareness about HIV/AIDS and engage the so-called “key populations,” such as gay and bisexual men, who were considered to be at high risk of contracting HIV.

Since that time, the akta community center has been conducting outreach activities to raise awareness and educate people about sexual health, including HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases, by visiting gay bars and clubs where these key populations are likely to be gathered. Since the center itself is located in the heart of the Shinjuku’s Ni-chome district, we have created a place where people can feel free to drop by. It is also used as a general “community center” for exhibitions and gatherings that are open to anyone, regardless of their sexuality. Before the spread of COVID-19, we had 8,000 to 10,000 visitors a year. These activities are actually based on a similar project in Australia.

Interior of akta’s facility in Shinjuku, Tokyo. Photo courtesy of akta.

Interior of akta’s facility in Shinjuku, Tokyo. Photo courtesy of akta.

Can you explain further about akta’s outreach activities?

Nowadays, HIV is less of a taboo in Shinjuku’s Ni-chome district, and more people are coming out to say that they are living with HIV. However, in the past, there was a strong sense of rejection from bars and clubs. We have been searching for ways to make people think about HIV/AIDS as “our” issue, very much existing in “our” city. There are about 400 gay bars in the area, and every Friday night we continue our “Delivery Boys” outreach to about 170 of them, distributing condoms and informational flyers. We also create educational materials that include interviews with owners of popular bars and “go-go boys” (club dancers/gay influencers), and we invite illustrators who are popular among gay men to design original condom packages, hoping that it helps people feel more comfortable accessing condoms.

Has akta changed the image of HIV in Shinjuku Ni-chome?

According to the Delivery Boys, when they enter a bar or a club, it opens up an opportunity for the bar staff to talk to the customers about HIV/AIDS and health issues, and conversely, the customers sometimes have deeper conversations with the staff afterwards. We analyze the information gathered this way to give feedback to the local and national health authorities, medical institutions, and other partners in order to improve their interventions.

Does akta serve as a “hub” that connects the Ni-chome district with government and expert organizations?

We always include people who are involved in HIV/AIDS policy in the community—local health authorities, medical professionals, and people from other NGOs—in our outreach activities. By having them actually walk around the area, we let them know the reality on the ground and change the image of what needs to be done to fight HIV/AIDS. The problem now is that they can no longer join in these visits due to COVID-19 restrictions.

In recent years, the UNAIDS “90-90-90 target” has been called a way to prevent the spread of HIV infections. Once the target is achieved, the number of new infections can be curbed. As a result, there are people who argue that we should focus on testing and that we no longer need these inefficient outreach activities. But in reality, unless we continue these grassroots activities, we will not be able to reach those we really want to reach. For example, while an estimated 85 percent of people living with HIV in Japan know their HIV status, which is higher than expected, we are still 5 percent short of raising this rate to the 90 percent target. Based on nationwide studies, we know that 5 percent is comparable to about 4,000 people, and these are the people that we have been struggling to reach.

We also work closely with support groups for people with drug and alcohol addiction issues, living in poverty, or with mental health issues in the hope of reaching out to hard-to-reach populations. The biomedical approach is important to achieve the ultimate goal of ending HIV/AIDS, but the only way to reach the remaining 5 percent is to stay in touch with the community.

を迎え、コミュニティと研究者との対話を開催。右端が岩橋氏-photo-credit©toboji.jpg) Peter Piot (far left), former Executive Director of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, visited akta for an engaging discussion with Iwahashi (far right), people from the LGBT+ community, and researchers. The event was co-hosted by akta and FGFJ in Shinjuku, Tokyo. ©toboji

Peter Piot (far left), former Executive Director of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, visited akta for an engaging discussion with Iwahashi (far right), people from the LGBT+ community, and researchers. The event was co-hosted by akta and FGFJ in Shinjuku, Tokyo. ©toboji

How did you become involved in this kind of work?

In 2007, when I was a university student, I attended a lecture by Professor Chizuko Ikegami, a sexology researcher, and learned that “sex and sexual health are human rights,” which sparked my interest in the topic. I began volunteering as a telephone counselor at PLACE Tokyo, a nonprofit in Tokyo that supports people living with HIV, where Professor Ikegami was the president at the time. I became involved in awareness-raising events for people living with HIV and gay bars in the Ni-chome district of Shinjuku, and later became interested in collaborating with local health and medical professionals. Then, the MHLW launched a major strategic research project for AIDS prevention for which I was a member of the research team. After that, I joined akta as a board member. I hope to maintain the viewpoint of a researcher, while serving as acting as a catalyst to connect various stakeholders.

From your standpoint, what do you think the challenges are in the fight against COVID-19?

Whether it is testing or vaccination, it is important to get the right information and tools to the right people, and this is no different from dealing with HIV/AIDS. In tackling HIV/AIDS, there is a term called “key populations.” The idea is that these are the people who are at high risk of infection, but at the same time, they are also the people who hold the key to achieving effective countermeasures. It is important to involve them in the planning, implementation, and evaluation, rather than excluding or simply labeling them as a high-risk group.

There is insufficient data sharing on epidemiological trends of COVID-19 in Japan. In the HIV/AIDS field, information on new infections is shared with NGOs that are engaged in prevention, awareness-raising, and support activities, but with COVID-19, perhaps because it is an ongoing pandemic, data on trends is not shared with NGOs or other organizations, and it is frustrating to be unable to grasp the situation in the neighborhood.

In addition, even if someone contracts COVID-19 in this neighborhood, some people may not be able to report exactly where or how the virus was transmitted. They may not even want to admit having been in the Shinjuku Ni-chome district. The problem is not with the person who is not willing to tell the truth, but with the society that doesn’t allow people to feel safe revealing their sexual identity, even when it is necessary. This makes it even more difficult to see the status of COVID-19 infection in the area.

We believe that akta’s role as a hub can also play an important part in the fight against COVID-19. In 2020, we held study sessions for people running the bars and clubs in the area, inviting doctors and government officials involved in the fight against COVID-19. Also, we have just started talking with the relevant organizations to see how we can apply our experiences of HIV testing and counseling to COVID-19 testing measures.

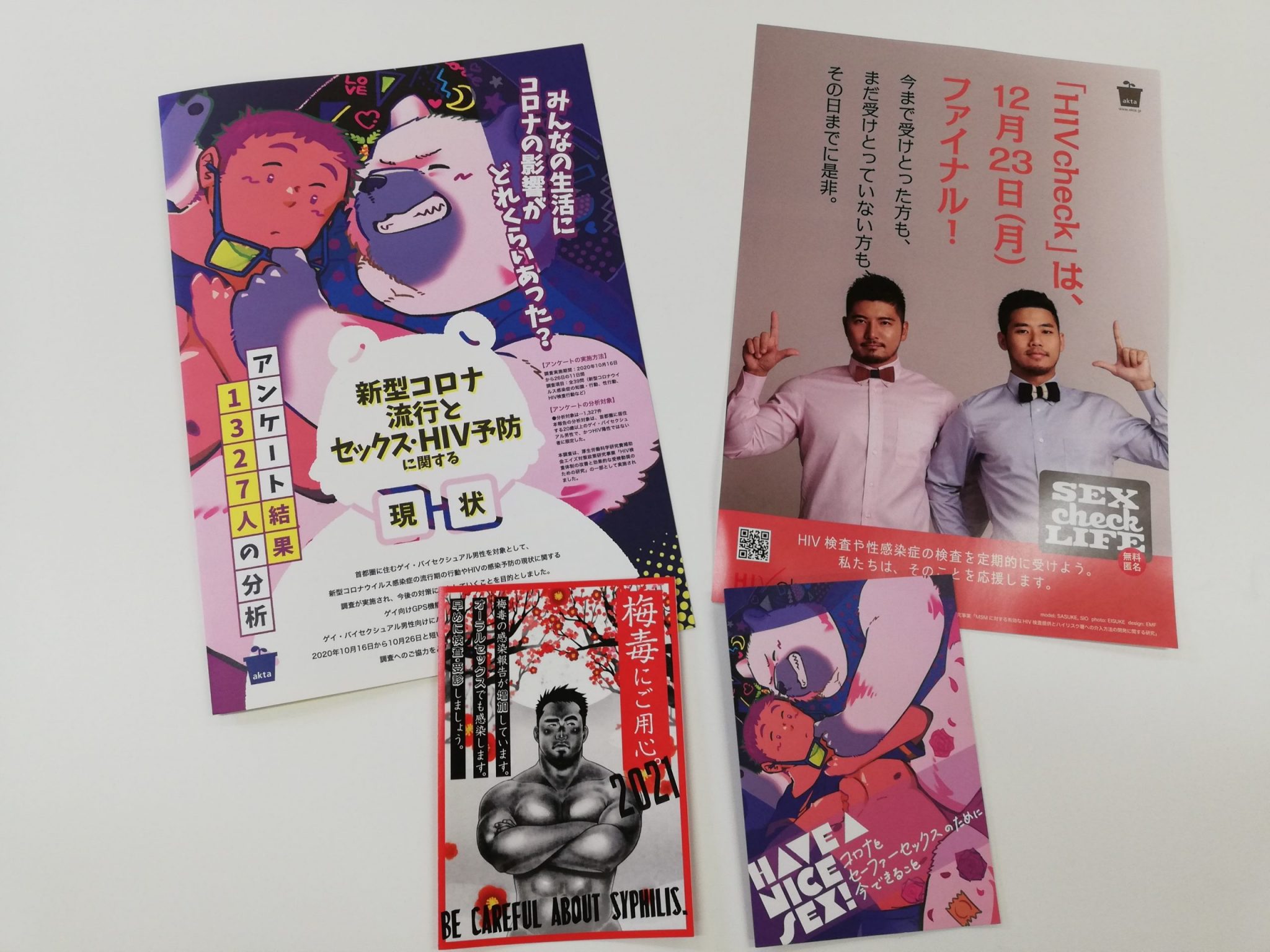

Educational materials on HIV and COVID-19 prevention prepared and distributed by akta. In addition to this, akta is also conducting a survey on coronas and sex life and providing feedback. Photo Courtesy of akta.

Educational materials on HIV and COVID-19 prevention prepared and distributed by akta. In addition to this, akta is also conducting a survey on coronas and sex life and providing feedback. Photo Courtesy of akta.

The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (the Global Fund), who supports testing efforts in low- and middle-income countries, argues that it is especially critical to maintain testing for HIV and other infectious diseases while fighting COVID-19. However, in reality, testing has significantly decreased during the pandemic. What have you seen in regards to HIV testing in Japan? Has this changed over the last year with the pandemic?

It is necessary to respond to the needs of people who want to be tested if they have any concerns about their health. And testing is also important to assess trends in the spread of infection. Yet in Japan, the movement to expand options for HIV testing is still limited, with public health centers and medical institutions playing a central role. Once these institutions are overwhelmed with the COVID-19 response, HIV testing will also be affected. In fact, at one point in 2020, the number of HIV tests conducted at public health centers dropped to just 25 percent of the previous year’s level.

Just saying “HIV testing at public health centers is free and anonymous” will not get people to come for testing. Similarly, it is possible that there will be people who are difficult to reach for COVID-19 testing and vaccination. If you allow that to happen, there is a risk that the handful of people left behind will become the “navel” (center) of a resurgence in the epidemic. So, I think everyone has to realize the importance of having a society where no one is left behind. In addition, although COVID-19 tends to be the current focus of attention, the HIV epidemic is far from over. Even under the COVID-19 pandemic, people will obviously continue to have a sex life, too.

In the UK, the number of people tested during the HIV testing week in February this year was four times that of the previous year, despite COVID-19. It is said that this is because a TV drama about the AIDS epidemic in the gay community in the 1990s became a hot topic, which, combined with the spread of COVID-19, raised people’s interest. At the same time, I was told that it was easy to take the tests, whether at the clinic or at home, using self-testing kits and shipping them by mail.

We can see that it is important to create resilient HIV/AIDS measures and systems despite COVID-19 and we are committed to continuing our activities, firmly rooted in the community of Shinjuku’s Ni-chome district.

About Kohta Iwahashi

About Kohta Iwahashi

Kohta Iwahashi is the president of akta, a nonprofit organization based in the heart of Shinjuku Ni-chome, a district said to host the largest community of sexual minorities in Asia. Since 2007, he has been involved in activities to raise awareness of HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections among male homosexuals in the Tokyo metropolitan area.

To read more interviews like this one, please visit the main “Infectious Diseases Without Borders—Our Story” series page.

For interview content in Japanese, please visit the Asahi Shimbun GLOBE+ website.