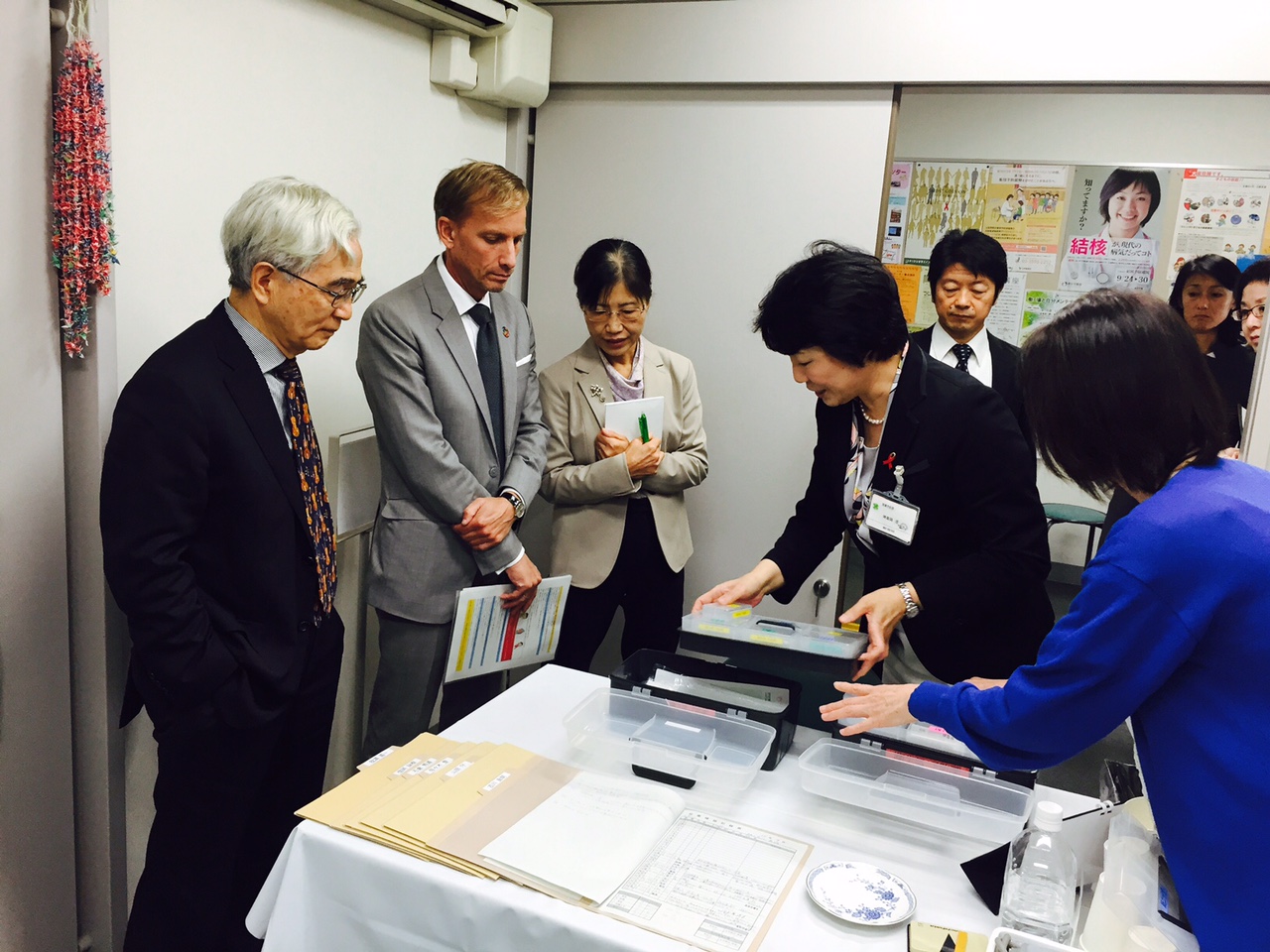

Mark Dybul discusses the Global Fund’s work on controlling the three major infectious diseases at the FGFJ Diet Task Force breakfast meeting. ©FGFJ 2015

This installment of the “Infectious Diseases Without Borders–Our Story” features Ambassador Mark Dybul, who decided to pursue a medical career to fight HIV/AIDS and ended up leading the American effort —and later the global effort—to battle the disease. In the 1990s, he set out on a career as a researcher, but was asked by the White House to help set up the US response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. He eventually rose to become one of the most prominent figures in global health. Here is the story of a doctor who ventured far outside of the clinic and into the world of politics.

“Infectious Diseases Without Borders–Our Story” launched last November by the Friends of the Global Fund, Japan (FGFJ), in collaboration with Asahi GLOBE+, the online media of the #2 national newspaper in Japan. This article is available in Japanese on the Asahi GLOBE+ website.

Q: How did you end up in the world of HIV/AIDS?

Like many things in life, it was an accident. I was actually a philosophy and theology major in college and thought I’d go into academics, but then I read an article about HIV in Africa. This was while I was still in college, and it really just grabbed hold of me. I can’t explain why, it just did. I then proceeded to get a degree in medicine because of that and started medical school in 1988. Back then, everyone who had HIV/AIDS was dying, so being a physician purely was very difficult. Most people were burning out after a year or two of caring for HIV patients.

Dybul walks with Fund Portfolio Manager for Central Africa, Gilles Cesari, across the border between Togo and Benin after a ceremony inaugurating partnerships between the Global Fund and authorities and associations working on HIV/AIDS programs and OCAL (Organisation du Corridor Abidjan-Lagos). ©The Global Fund / Sam Phelps 2017

So, I went into research hoping that I could contribute in some way, and the chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of Chicago was friends with Tony (Anthony) Fauci, so he connected us. I interviewed with Tony for a National Institutes of Health (NIH) fellowship in infectious diseases. Ultimately, I ran a section of his lab. We actually ran the first randomized controlled trial including anti-retroviral therapy in Africa. Then, when President Bush decided he wanted to do something big on HIV, he turned to Tony, as President Biden recently has on COVID. Tony and I put together, with people in the White House, what became the implementation plan for the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and from there, I ended up running PEPFAR, and then ultimately The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund).

Q: You worked for many years in the Bush administration on HIV/AIDS issues, and headed PEPFAR from 2006 to 2009 as the US Global AIDS Coordinator, so you knew the Global Fund very well. But what did you learn about the Global Fund after you were appointed as its Executive Director in 2012?

There are many things you don’t know outside of an organization until you get inside it. The first thing that I learned was how diverse and talented and committed and passionate the Global Fund Secretariat team is. More than 100 nationalities are represented in a Secretariat of around 700 people. That’s pretty extraordinary. And the commitment to the cause and the “mission-drivenness” of people from radically diverse backgrounds and completely different cultural perspectives was really extraordinary.

And the second thing was how much countries really value the Global Fund. It actually used to annoy me when I was at PEPFAR when I went to events with the heads of state or ministers, and they would always talk about the Global Fund and not PEPFAR. But then I got to understand why. The Global Fund really is embedded with and supports the countries and the people in the countries. You cannot drive change on a national scale from a bilateral program. It’s got to be owned by the country, and the Global Fund does an exceptional job of supporting the countries and building the capacity of their health systems.

©FGFJ提供.jpg)

Dybul participates in the FGFJ Diet Task Force Breakfast Meeting with Bill Gates. © FGFJ 2015

Q: When you started out in your career, HIV/AIDS was a death sentence. What have you seen change in people’s everyday lives since then?

I’ve had the great privilege to go to the same villages 15–20 years later. Seventy-five percent of pregnant women in some districts were infected with HIV. The life expectancy was cut almost in half in the hardest hit countries over the course of a couple of years because of one disease. And what that translated to in individual terms was that every person knew someone who had died. If you went to someone’s home in a village, they usually had the family buried in front of the home. Entire villages were run by orphans because all of the adults had died. What really strikes you in that environment is how hopeless things were. Why would you educate your child, why would you try to get a job if you are certain that you are going to die from HIV? The palpable hopelessness was remarkable.

In contrast, now when I go back to the same villages and meet some of the same people I met 10 or 15 years ago, they’re vibrant and hopeful. One of the reasons that Africa was the second-fastest growing economy in the world until COVID was because the hopelessness had been converted to hopefulness. It was touching individual lives and changing how they looked at themselves, their communities, their country, and their place in the world, literally. You meet young kids and talk about, “I want to be an astronaut,” “I want to be a pilot,” “I want to be a doctor.” A lot of them talk about wanting to go into healthcare and wanting to serve others and engage. And that’s really just an extraordinary thing. We see the numbers but what really changed was so palpable in individual lives and at the community level. The value of that is incomprehensible.

I’m still in touch with people I met in the early days, especially with pregnant women who were HIV-positive. I met one woman in Namibia who named her child “Hopeless.” The notion of naming your child “Hopeless,”….to have a child is the most hopeful thing in the world. She was infected and was certain her daughter was going to become infected and die. But she’s had several kids since, all of whom are alive.

Dybul visits Syrian refugees in Zaatari Refugee Camp, Jordan. ©The Global Fund / Tanya Habjouqa

Q: Japan has a low prevalence of HIV/AIDS, TB is not a major issue, and it doesn’t have malaria, so, why should Japan care about the Global Fund?

We have to remember, the Global Fund was born in a G8 Summit in Okinawa, and there are several big reasons for Japan to continue to care. One is that deep experience that Japan brought to the world, and it is now able to support others with leadership from its own experience. That leadership role has been transformational for the world. The push for universal health coverage comes from Japan.

Another is that Africa is the second-fastest growing region in the world, and you can trade with a growing economy, so there’s a strong self-interest for Japan in fighting HIV/AIDS in Africa.

And if we don’t have a healthy world, we have no hope. In health, no one is safe until everyone is safe from infectious diseases. And the way we move around the world, which is good for our economy, means we’re going to have these constant threats. Nowadays, the economy of Japan is just as susceptible to a pandemic as an economy in Africa.

Dybul visits the tuberculosis department at the Shinjuku Public Health Center in Tokyo, Japan, guided by Nobukatsu Ishikawa, Director of the National Institute for Research on Tuberculosis. © FGFJ 2016

Q: One of the main characteristics of the Global Fund is its focus on the three deadly diseases, but now it is also working on COVID-19. Why is it well positioned to help with COVID-19?

It’s well positioned because it is now fully embedded in governments and in countries as a key part of the health system, including in terms of “how do you procure products, how do you support logistics and supply chains, and how do you have community healthcare worker networks that will be the ones to detect a new outbreak and lead to a rapid response to an outbreak?”

Just look at what South Africa did. South Africa fielded 28,000 community healthcare workers to do contact tracing. In Sierra Leone, there were 9,000 community healthcare workers. The United States didn’t even reach those levels. This all came from investments in HIV, TB, malaria, maternal and child health, and vaccination. The Global Fund has been investing in these things which is why a recent study pointed out that one-third of the investments that the Global Fund makes are directly related to and useful for global health security. So, the Global Fund is extremely well-positioned to play a key role, not only in the response to COVID but in pandemics for the future.

Farewell event for Dybul as he finished his term as the Global Fund’s executive director. © The Global Fund

Q: How do you assess Japan’s work with the Global Fund and its international contributions?

I would like to thank the people of Japan for the G8 Summit in Okinawa, without which there wouldn’t be the Global Fund, and for the extraordinary leadership that Japan has shown, not just in providing financing, but in sharing technical expertise in global health and in pushing for equity and universal access to healthcare as a global cause. Without Japan’s voice for the last few decades, that wouldn’t have happened. Without Japan’s engagement, the Global Fund wouldn’t be where it is today. There can be great pride in what Japan has accomplished but also the opportunity to continue to lead and drive, to change the world.

About Mark Dybul

About Mark Dybul

Ambassador Mark Dybul MD is the co-director of the Center for Global Health Practice and Impact, and a professor in the Department of Medicine at Georgetown University Medical Center. He is also a Chair and Fellow with the Joep Lange Institute. A well-recognized global health expert and humanitarian, Dr. Dybul has served as executive director of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria from 2012-2017. He also served as a HIV research fellow at the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) under director Dr. Anthony Fauci in the late 1990s. Dr. Dybul conducted basic and clinical HIV research at NIAID, and eventually conducted the first randomized, controlled trial with combination antiretroviral therapy with HIV patients in Africa. He went on to lead President George W. Bush’s International Prevention of Mother and Child HIV initiative for the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and in 2006 was named U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator. As U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator, he led the implementation of PEPFAR, a health initiative Dr. Dybul helped create. He later became the inaugural Global Health Fellow of the George W. Bush Institute.

To read more interviews like this one, please visit the main “Infectious Diseases Without Borders—Our Story” series page.

For interview content in Japanese, please visit the Asahi Shimbun GLOBE+ website.